Markus Meister

A talk presented at the Symposium “Vision and Mind”

University of Cambridge, Dec 2022

In late 2022 I was invited to a symposium in honor of Horace Barlow, who had passed away that year. It was a wonderful occasion, the arctic cold of Cambridge UK contrasting with the warmth of Miranda Barlow’s house and the fellowship of the guests that had come from around the world. Here is an approximate transcript of my remarks, remembering Horace through his scientific papers.

The scientists to whom I owe the most all passed away recently. Two of these – Howard Berg and Denis Baylor – I talked with every day for several years of my life. Horace Barlow, on the other hand, I met only twice at conferences. I really know him almost exclusively through his writings. So I won’t have any personal anecdotes to share, but instead want to focus on the scientific papers that left such a strong impression on me. Obviously this is but a small selection.

Looking back at my notes, I first came across Horace’s legacy as a beginning graduate student. This was perhaps the first term paper I wrote in graduate school, trying to mix some ideas from a course about Shannon’s information theory and another on neuroscience. The question was how much information compression the retina can achieve for the visual image – something that sounds familiar to many in this room. After this course I went on to measure cosmic rays in interplanetary space, and then wrote a PhD thesis on how bacteria swim. But ten years later I found myself as an assistant professor, building my research around the topic of this paper, namely information processing in the retina.

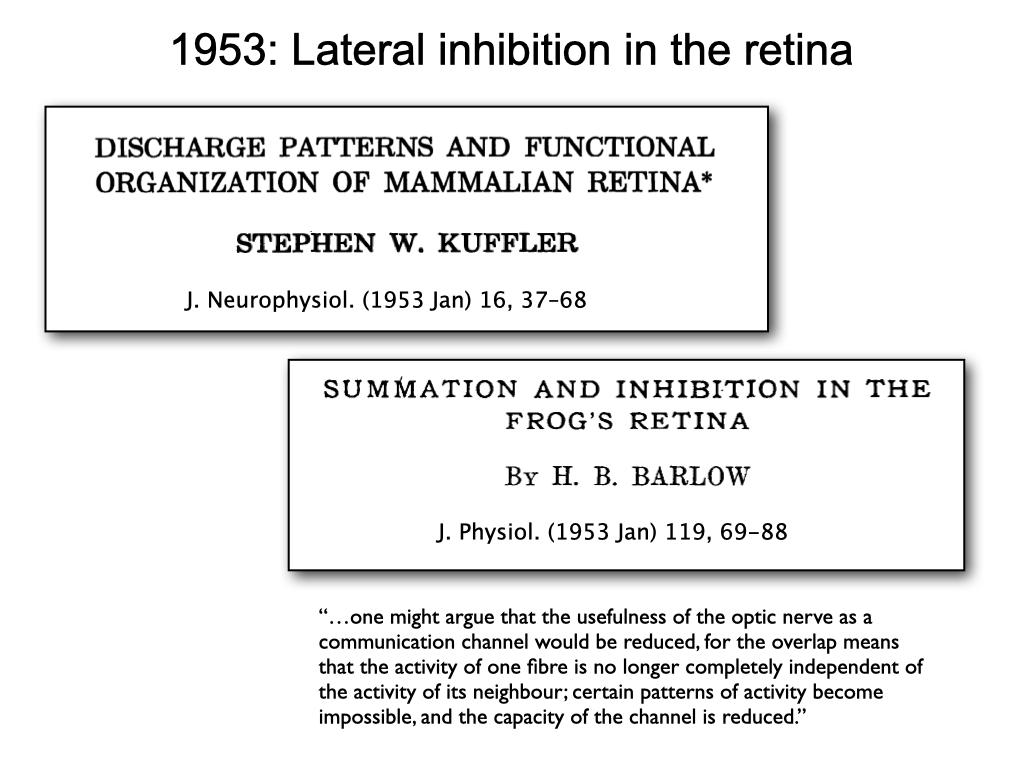

Let’s take a look at Horace’s first foray into this area. His 1953 paper on lateral inhibition in the vertebrate retina appeared in the same month as Steve Kuffler’s. These two giants of neuroscience reported what we now understand as the same phenomenon. But they came to the subject with very different styles. Steve reports the study in a workman-like and systematic manner: “first we did this, then we did that”. Horace, instead, starts the paper with a long disquisition on what one ought to expect to find, before even doing the measurements. He takes issue with an earlier report by Hartline that ganglion cells have large receptive fields with a lot of overlap. This would mean that nearby ganglion cells almost always report the same message about the image. That offends Horace’s sense that the visual system should be efficient, and so one needs to look into this with better methods. All this happens before he reports any results. I wonder sometimes how many readers fully appreciated these introductory paragraphs at the time. Obviously Horace is concerned with high-level principles behind sensory systems, but what exactly are those principles? We will get to that in a little while.

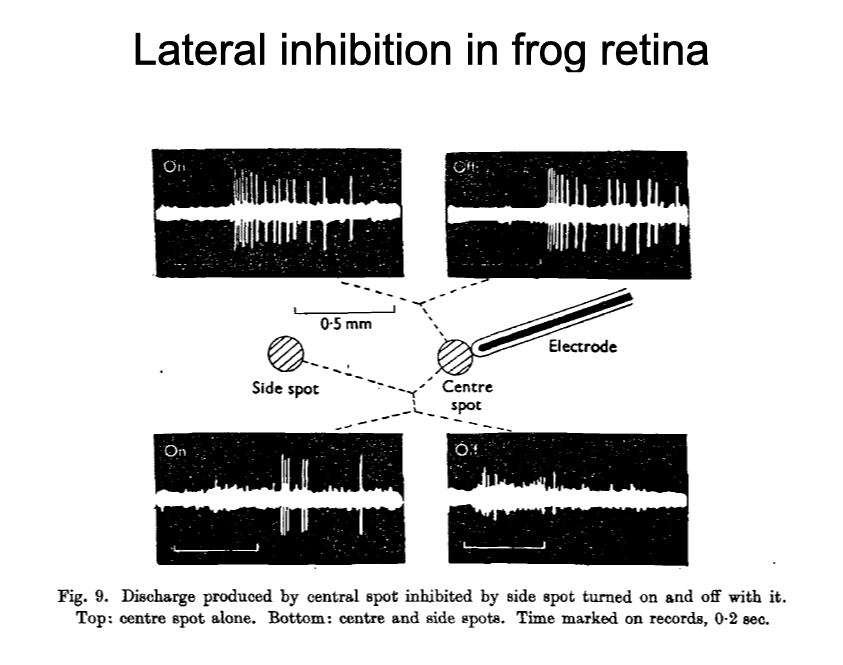

Among other things, Horace demonstrated that light has different effects depending on where it falls on the retina. A small spot of light close to the recording electrode produces a strong burst of spikes. But if you add another side spot at the same time, the response is much smaller. This was termed “lateral inhibition”. Clearly the ganglion cell doesn’t just sum light from a large receptive field, as Hartline had proposed. Instead it subtracts light in one region from light in another region. This confirmed to Horace that the retina performs much more interesting processing than previously thought. In particular, a uniform stimulus, which is a very common pattern in nature, produces only a weak response, and the retina mostly signals deviations from that expectation.

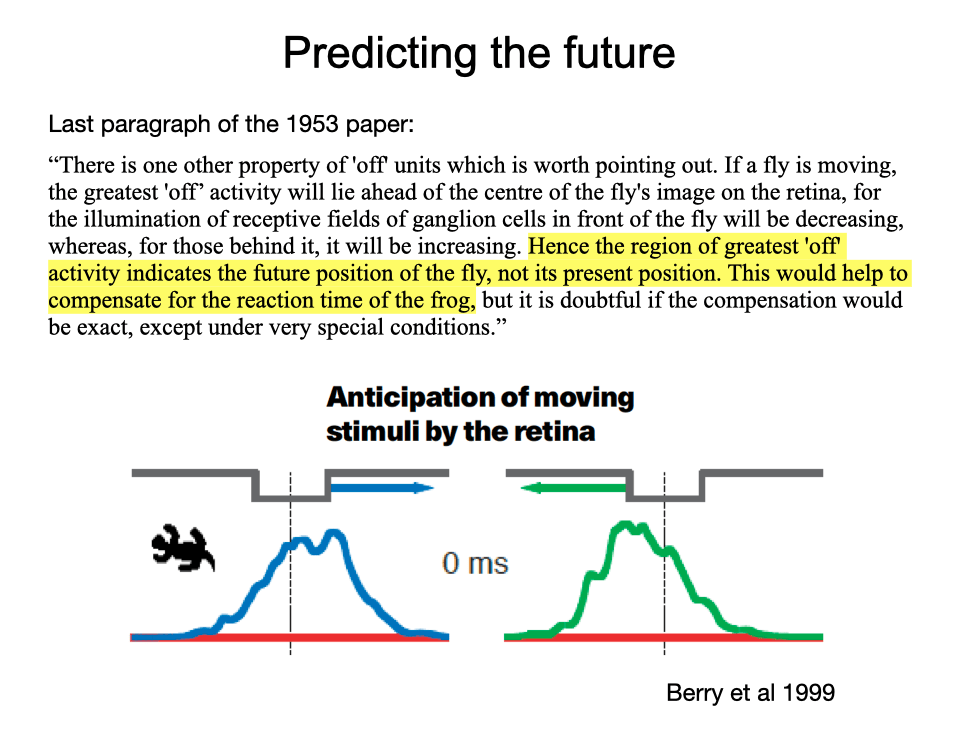

As is customary in Horace’s papers, there is also a glimpse of the future. In the last paragraph of the 1953 paper, Horace extrapolates from the reported measurements to what the retina of the frog might do with an important ecological stimulus, like a moving fly. He thinks a moving object should produce a wave of activity among ganglion cells that rides ahead of the object’s true position. This seems counterintuitive, given the response delays in photoreceptors, but is in fact exactly what happens. Some decades later, we were able to show that by recording simultaneously from an entire population of retinal neurons.

Here we come to a hugely influential article from 1961. It is published as a book chapter, so you can’t actually find it in the common literature databases. The paper also has no figures. It is all about concepts. But it uses figurative language, as illustrated by these snippets.

Horace asks “why” the brain works the way it does, not “how” it works. To me this was a refreshing revelation. When I wrestled with this paper, I had just started my professional life at Harvard in the department of Molecular and Cellular Biology. Among my colleagues it was considered taboo to ask why a biological object was built the way it was. You were to focus strictly on mechanism, and ask “how”. The “why” questions just led to fuzzy thinking that could never be tested rigorously. Better left to the people in that other Harvard department for Evolutionary Biology. I have to think that Horace experienced similar pressures early on. The 1960s saw the rise of molecular explanations in Biology. And the Cambridge department was under the heavy influence of Hodgkin and Huxley and their success at bottom-up mechanistic modeling. So I suspect that he is reacting to those trends in this paper.

So what did Horace suggest is the purpose of sensory processing? The article considers a wide range of explanations, but eventually focuses on these ideas:

1. The first purpose is to search for patterns in the sensory data that are of likely interest. For example the image of a face or a familiar object. Such patterns by necessity reflect redundancy in the data. This means that some of the pattern can be predicted from knowing another part. For example, faces are symmetrical, so you can predict the right half from knowing the left half. Redundancy also has a strict technical meaning in the context of information theory.

2. The second goal of the sensory system is to reformat the signals so these special patterns are encoded very efficiently with just a small number of spikes. In the course of doing that, the redundancy gets reduced. There are fewer patterns left in the output signal than in the input. So the core hypothesis of this paper is often quoted as “redundancy reduction”.

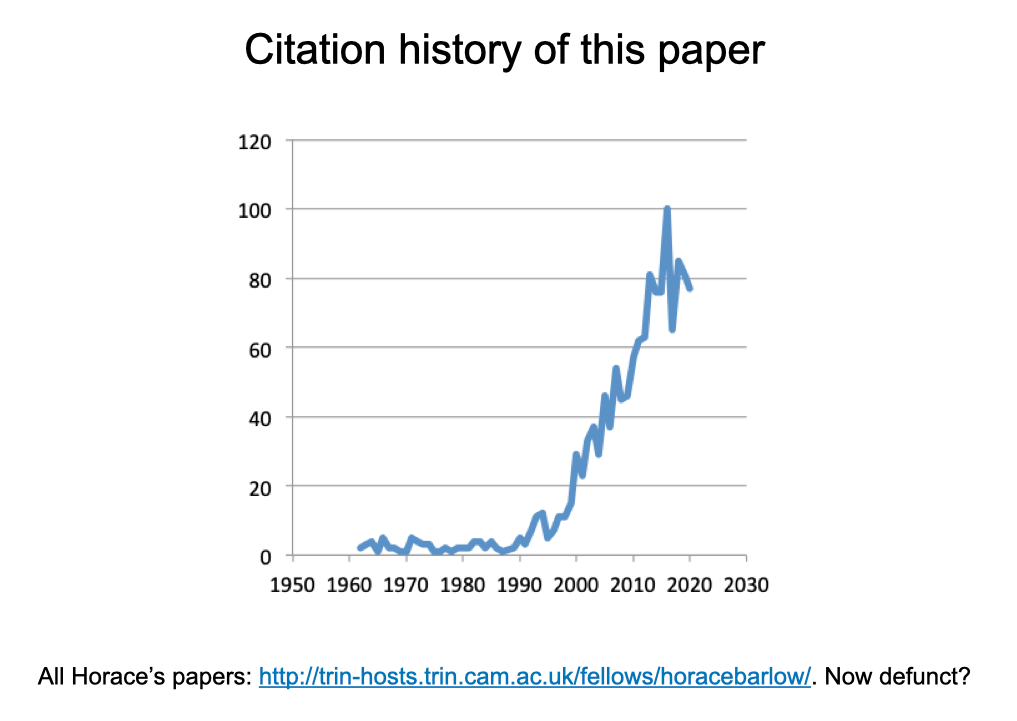

This paper has an interesting citation history. For about 30 years, there was no resonance in the community. Then suddenly around 1990, the citations start taking off, and popularity has grown every year since. So if you are a young student wondering what will be the next hot topic in neuroscience, I suggest reading Horace’s papers from 30 years ago for suggestions. He really was 30 years ahead of his time.

But where could an enterprising young student find that paper? Some of them are in remote book chapters and hard to find. Trinity used to have a web site that archived all of Horace’s writings, but somehow it has gone defunct. I think it’s time to rebuild and advertise such an online resource.

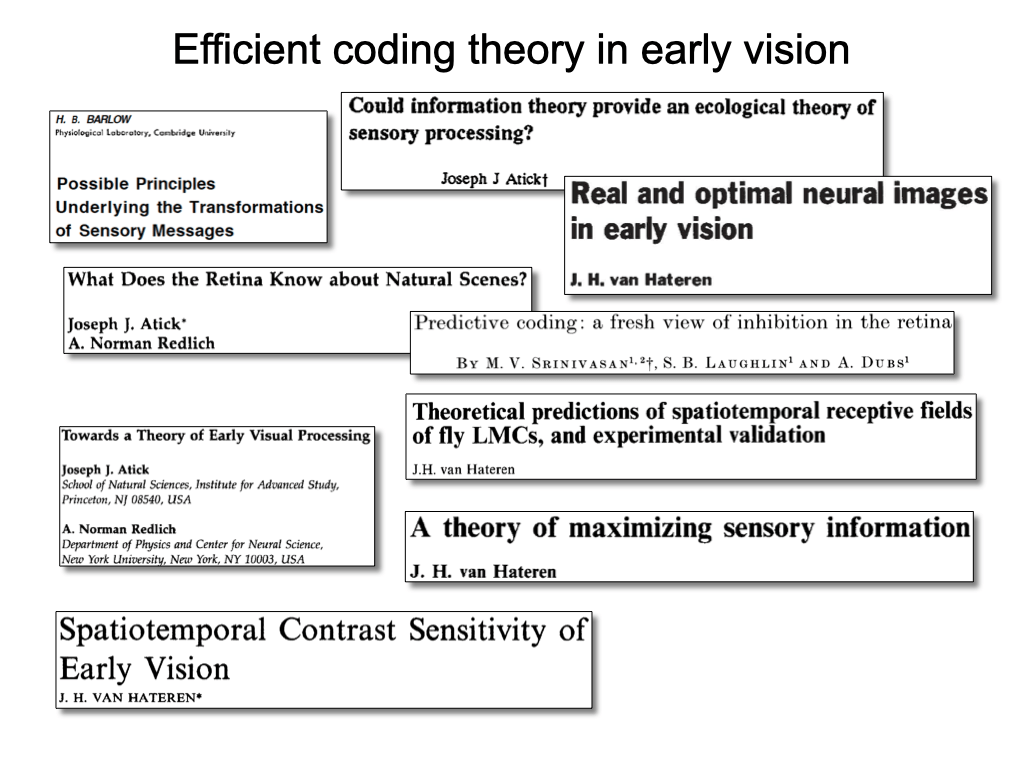

So what actually happened in 1990? That’s when the power of Horace’s ideas was recognized, and it produced an explosion of work on efficient coding theory. Today this framework forms one of the few normative principles in theoretical neuroscience. The papers here are picked from vision research, but the same ideas can explain a remarkable range of structure and function in other sensory systems. It appears that the efficient use of neural impulses really is a important design criterion for the nervous system.

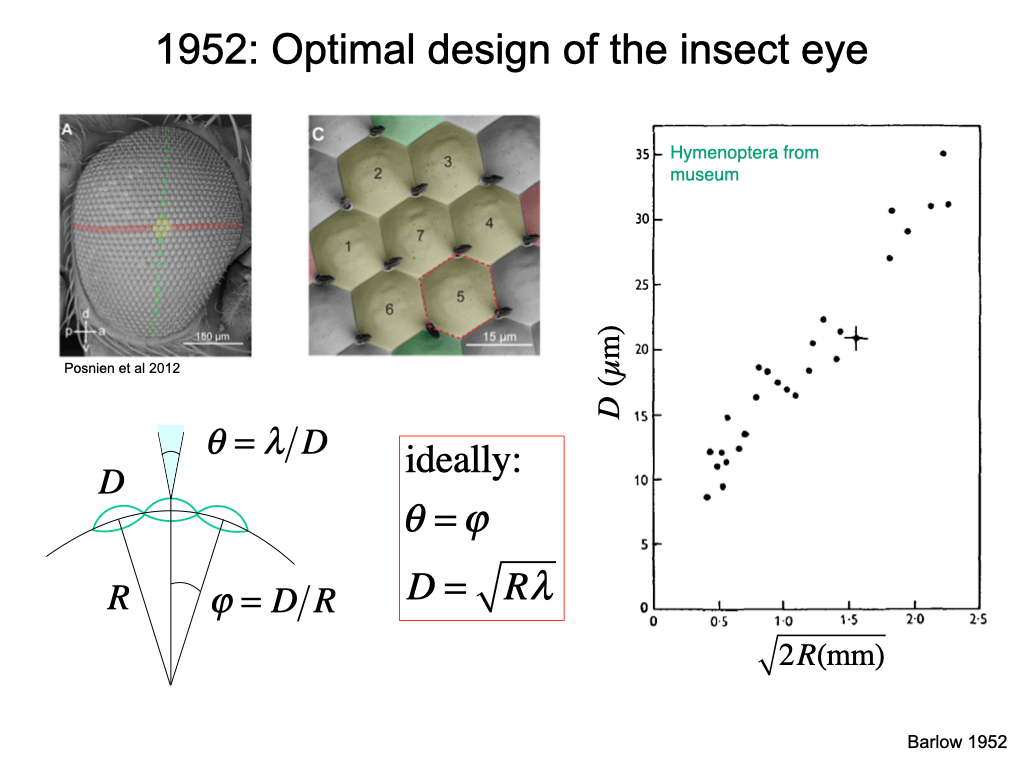

Speaking of design criterion, let me return to an earlier paper from 1952. Here Horace wonders about the optical design of the insect eye. Insects, as you know, have an eye with many hundreds of little facets.

Each facet is a tiny lens, and it looks out into just one direction of space, and reports the intensity there. So how big should such a facet be? If you make the lenses smaller, you can obviously fit more of them onto the surface of the eye, so the directions in space get sampled more finely. You might think that is good for spatial resolution. But if you make the lens too small then you get bit by the diffraction of light: A small lens collects light not just from one direction, but from a whole cone of light, and the acceptance angle increases as wavelength divided by lens size. So there’s a tradeoff between sampling density and this directional smear. The optimal setup is when those two angles are about the same, and that suggests the lens size should grow as the square root of the eye size.

With this prediction in hand, Horace went to the local Museum of Comparative Zoology, opened some drawers with species of hymenoptera, and measured their eye size and facet size. And in fact, the eye size (R) and facet size (D) vary together in just about the predicted relationship. An interesting case of optimal design in Biology.

This is another example how asking the “why” question helps in understanding. We no longer have to remember the facet size of all thirty of these insect species. It’s sufficient to know the principle along which the eye is designed. If you’re trapped on a desert island, you can recreate this argument by drawing lines in the sand, and easily reproduce all these facet sizes.

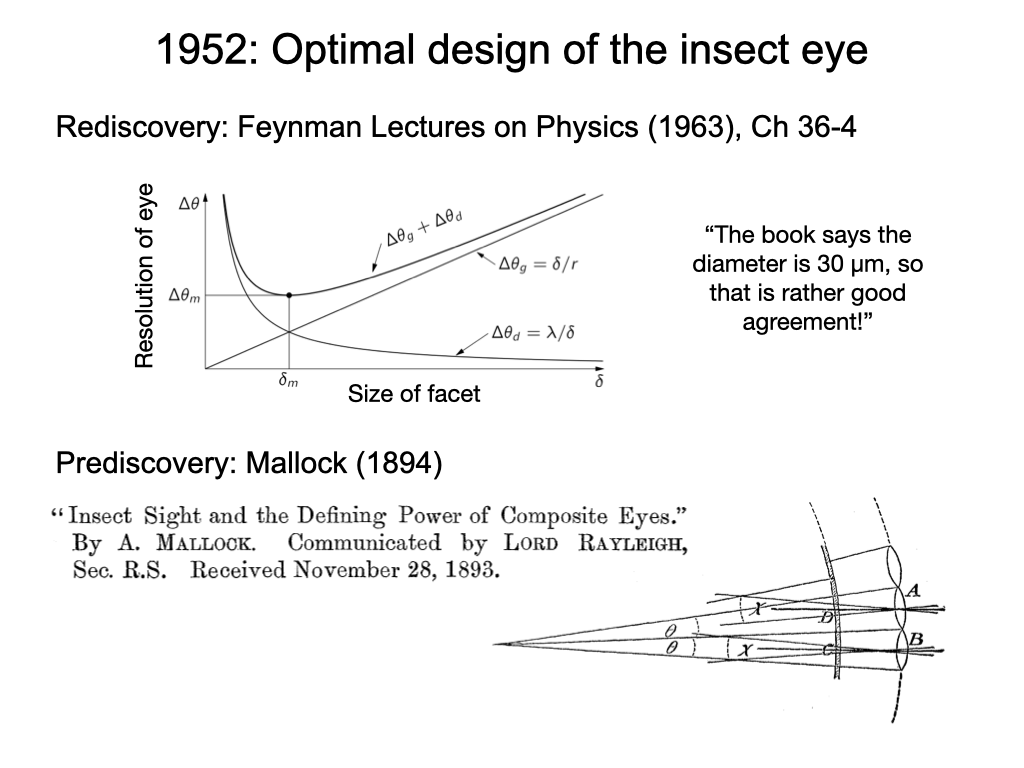

Incidentally, this beautiful problem seems to get rediscovered periodically. Feynman (1963) presents a derivation in his Lectures. In typical physicist fashion, he looks up the dimensions of just one insect eye, and is happy to declare victory. And there is also a “prediscovery” in a paper from A. Mallock in the 19th century.

Finally, this drawing from Kuno Kirschfeld reminds us that even the most beautiful theory in Biology has a limited domain of validity. If we extended Horace’s formula for optimal eye size to the spatial resolution of human vision, this is how we would end up. Obviously Nature has hit upon an alternative design for the eye of vertebrates, using a single large lens shared by all the photoreceptors, which fits into a much smaller package.

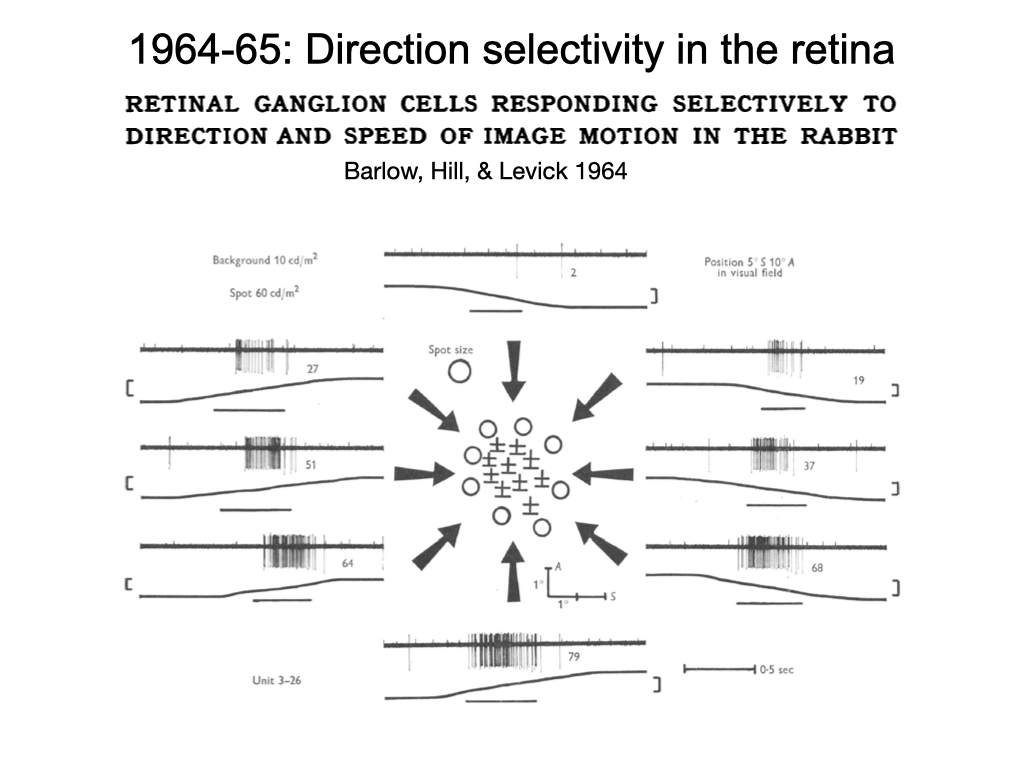

During the early 1960s, Horace spent time in Berkeley, where he worked with Richard Hill, Gerald Westheimer, Bill Levick and other vision scientists. Westheimer tells an anecdote that Horace was on an exploratory trip to Berkeley, when they visited Hill in his laboratory, who was recording from some cells in the rabbit eye. Horace was intrigued and waved a flashlight at the ceiling. When he waved it one way the neuron fired, but when it waved back the cell stayed silent. Apparently this was the discovery of direction selectivity in the retina. Here they plotted the receptive field of a retinal ganglion cell. When a small spot of light moves from bottom to top the cell fires a lot; when the spot moves the opposite way there is silence.

Parenthetically I’m not sure we could make such a serendipitous discovery anymore. In those days, you recorded from one cell at a time, and the spikes from the electrode were fed to a loudspeaker in the room. So you could hear exactly what the neuron signaled while you explored all kinds of stimuli. These days people record from 1000 cells at the same time, and you can’t put them on a loudspeaker. So you find out what they did only the following day after a lot of analysis, and you can’t change the stimulus until the next recording.

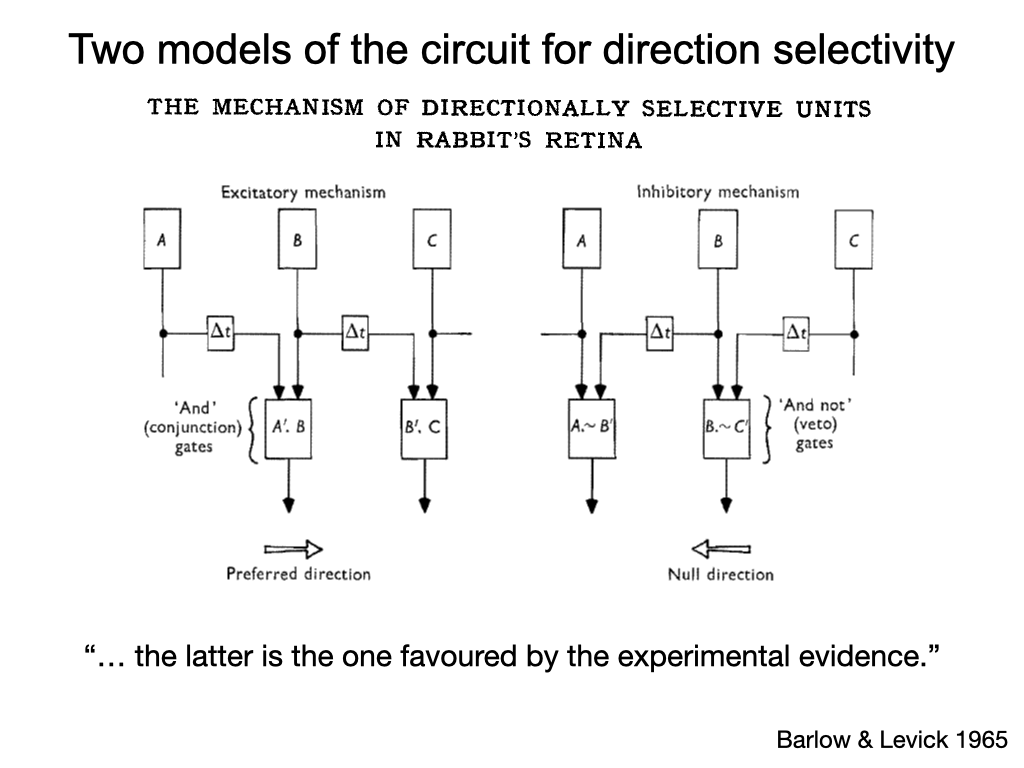

Barlow and Levick proposed 2 models for how this might work – note that’s twice as many models as in a typical neuroscience paper. And their analysis strongly favored one of the two, in which there is an asymmetric inhibitory connection. After much back and forth over the past half century that idea still stands.

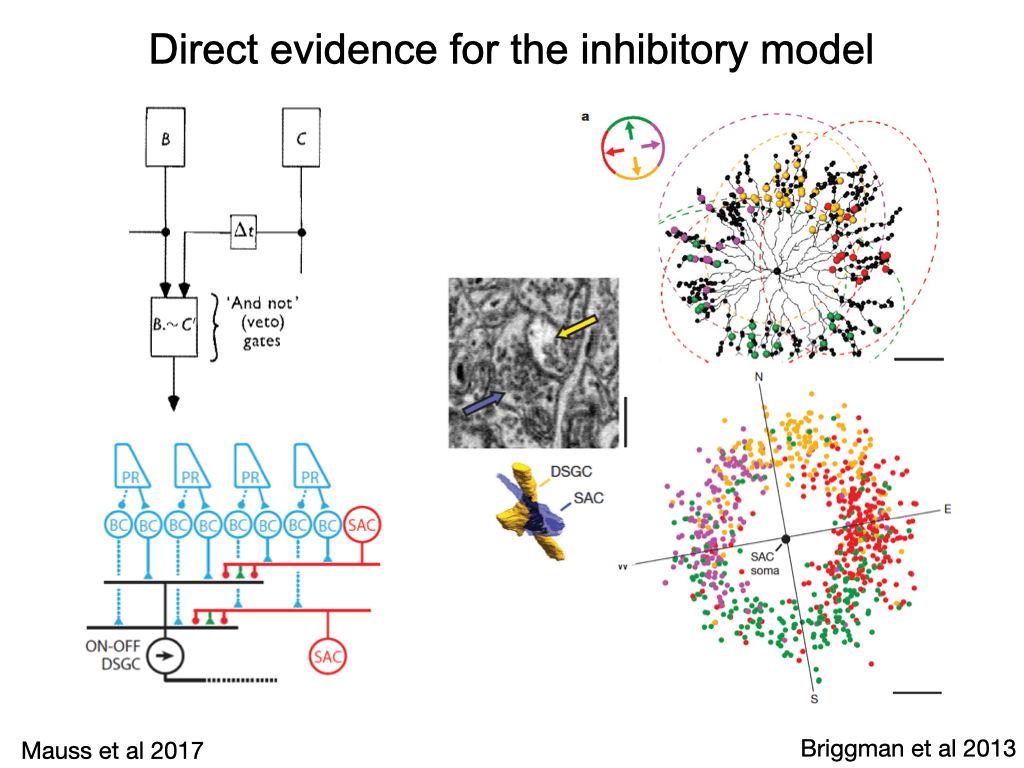

We now know that the sampling elements B and C are bipolar cells, the summing element is the ganglion cell, and the delayed inhibitory signal comes via an amacrine cell, called “starburst amacrine”.

Of course the important part of the model is the asymmetry: the amacrine cell should send its signal only from right to left, but not from left to right. This was finally verified 50 years after the proposal by painstakingly reconstructing the synaptic connections in the retina through electron microscopy. In fact, a ganglion cell that prefers upward motion gets its inhibition only from starburst cells in the downward direction.

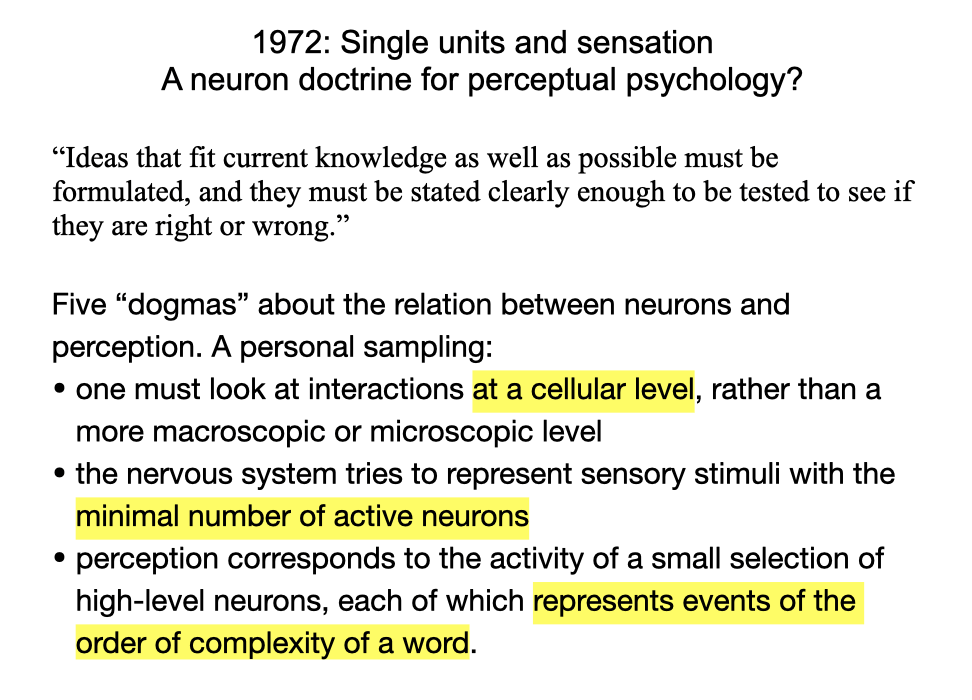

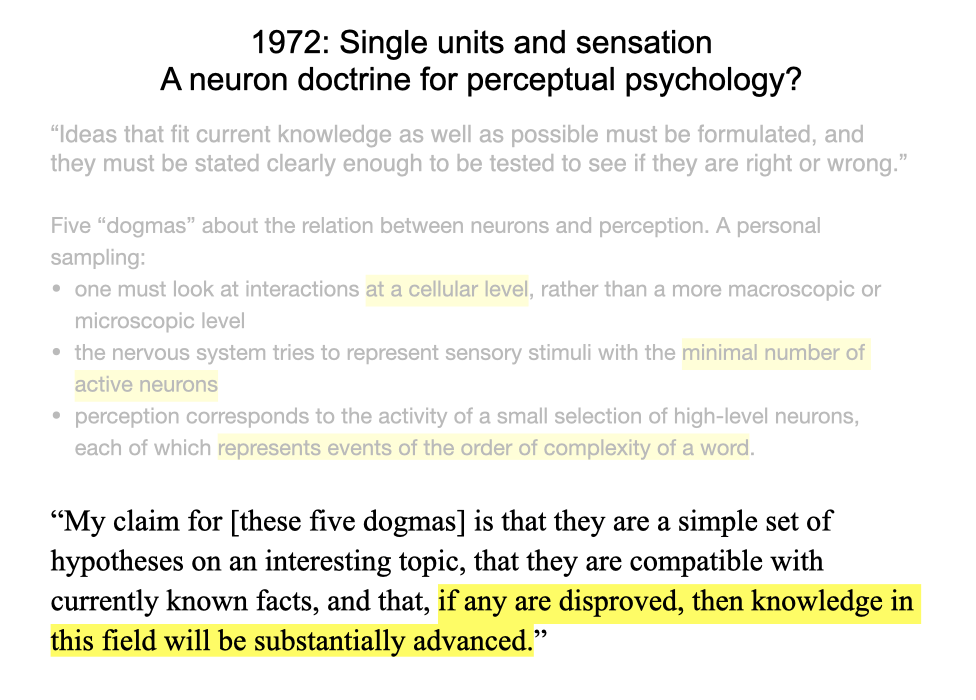

This 1972 paper comes closest to a manifesto, in which Horace lays out his deep beliefs about how the brain is organized. It has had an enormous influence on by now several generations of neuroscientists. Each of us can read this and find something different that catches your attention. In fact every time I read it I find new insights.

Horace wanted to draw some conclusions from what – even 50 years ago – was a profuse wealth of data about the brain. What have we learned from all this at a high level? And he sets out to summarize this by a set of principles that are consistent with the available evidence but go substantially beyond it. He presents these ideas in terms of dogmas. I suppose he was inspired here by the central dogma of molecular biology. But the statement was also intended to challenge people and invite critique. I won’t delve into the dogmas in detail, but I think these are three ideas that have had a great deal of resonance:

First Horace says you need to understand the system at the level of single neurons; not at the level of molecules; and also not at the level of brain regions. The essential action is close to the single neuron level.

Second, the sensory regions of the brain try to represent what is out there using the minimal number of active neurons. As one moves from the periphery to more central regions, the fraction of active neurons gets smaller and smaller.

Third, as the final result of this, he suggests there may be neurons whose firing signals a rather complex event, something on the scale of a word, that forms a substantial component of our perception. A picture is worth 1000 words, so he suggests there may at any time be 1000 neurons that represent the content of our visual perception.

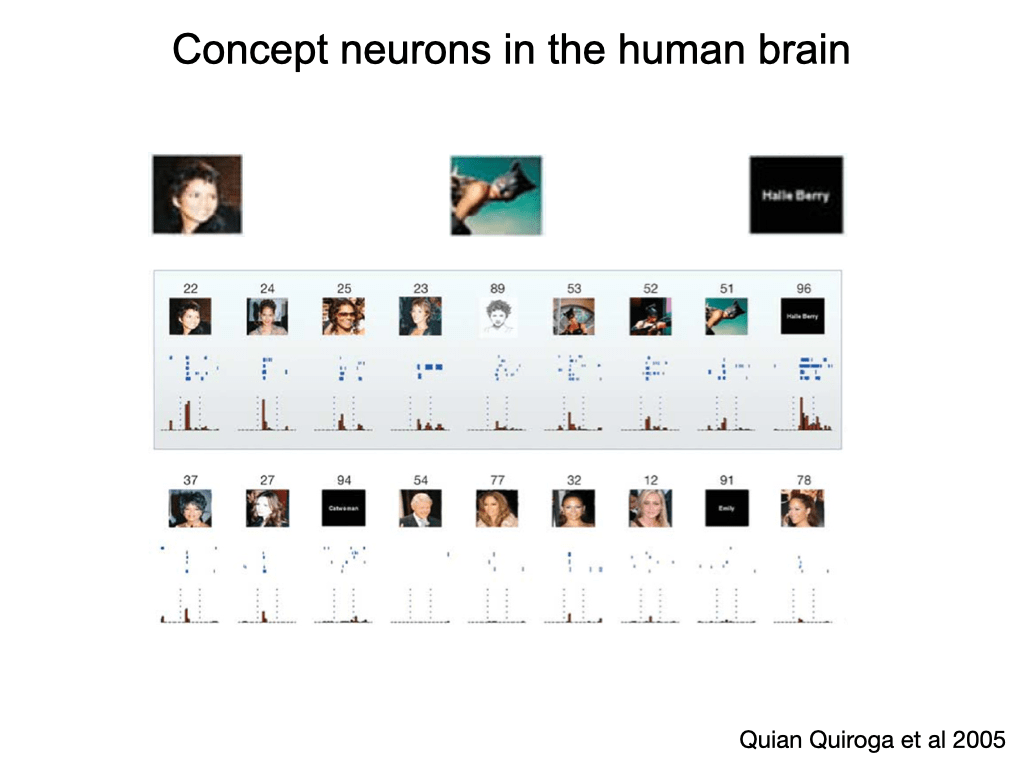

Some 30 years later, this idea got a great boost, through the discovery of single neurons in the human brain that are selective for high-level concepts, like Halle Berry. This neuron in an epilepsy patient fired in response to pictures of Halle Berry, her name in writing, or a picture of cat woman. But not when presented with all kinds of other actors or objects. Not surprisingly, Horace’s manifesto is the first citation in this report. This has turned into a very lively area of human neuroscience.

Finally, Horace insists that such principles should be stated in such a way to be falsifiable. And that, in fact, disproving his claims would be a sign of progress. Another attitude that has fallen out of fashion with current authors.

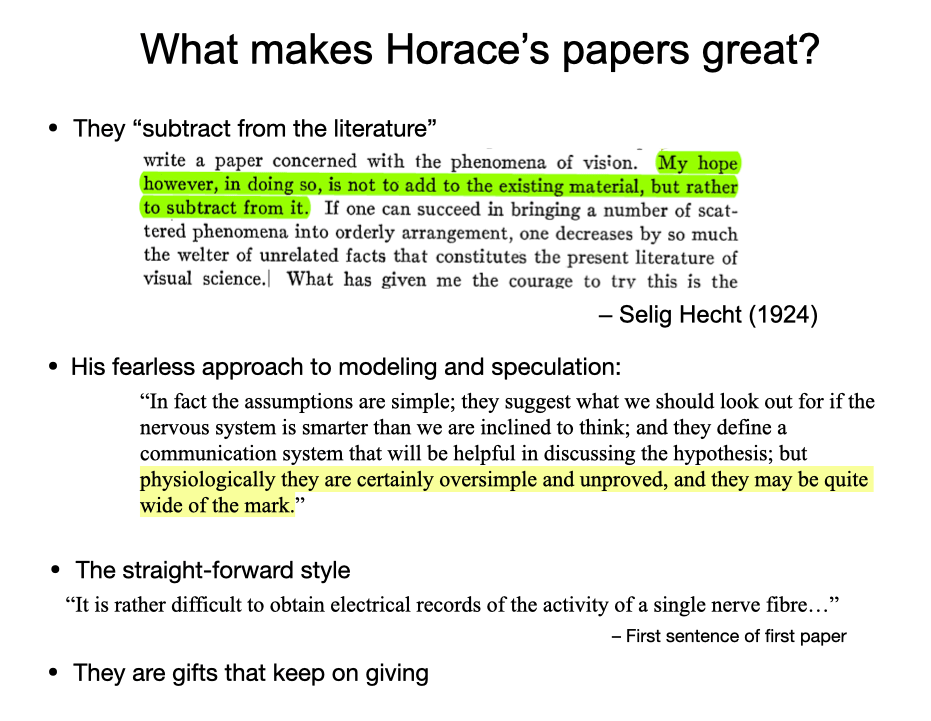

So let me close then by summarizing why I find Horace’s writing so inspirational.

For one, his papers “subtract from the literature”, in the sense coined by Selig Hecht. They can reduce a jumble of facts reported in a flurry of publications to a simple principle that ties those facts together. Interestingly, Selig Hecht failed in this particular instance, whereas Horace more often than not succeeded.

To accomplish such a reduction, one obviously has to look beyond the certified data and speculate a bit. Horace was always on the lookout for such overarching hypotheses, even – as we saw – in preparation for experiments, not as an afterthought. And he had no fear of missteps along the way.

Finally, they are such a pleasure to read, because of the straight-forward writing style, free of any obfuscation. Every time I read one of Horace’s papers I find a new nugget in it, because it connects to something I happen to be involved with at the moment.

With that let me thank you all for your attention, and I so look forward to the celebration of Horace’s work at this meeting.